Could Germany run out of gas?

31/08/2022

As the summer draws to a close and we all hunker down for the winter, European policymakers, businesses, and households alike are dreading the cold weather a little more than usual. Russia’s by now familiar weaponisation of natural gas has led to a unified effort by governments to fill underground reservoirs of the fossil fuel ahead of winter, in order to secure both everyday comforts and industry. Much of the media focus has centred on target storage levels going into the winter, but there has been less coverage of what happens next and whether Europe could truly run out of gas.

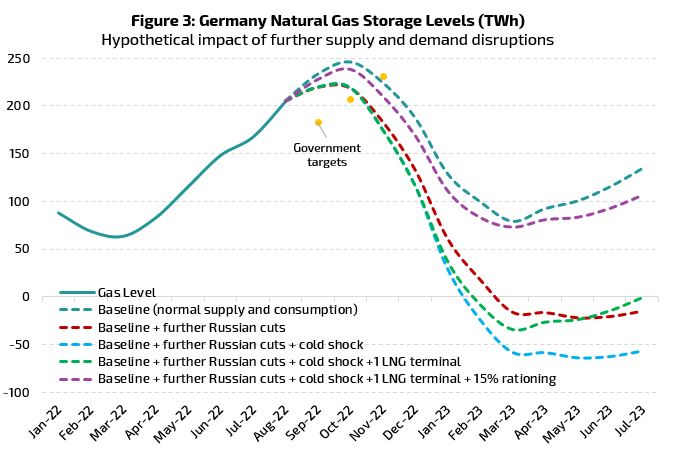

In our view, the discussion around storage level targets distract from the more important drivers of energy security, namely gas consumption patterns and ongoing new supply through winter. To see why, consider Europe’s industrial powerhouse Germany, where annual gas consumption during colder months is around 700 Terawatt-Hour (TWh). The German government hopes to achieve stored gas levels of 207 TWh (85% capacity) by 1st October and 231 TWh (95% capacity) by 1st November; it is easy to see that alone this simply isn’t enough to see the country through winter. But this is not unusual and even without Russian interference, Germany typically imports an additional 500-600 TWh worth of gas to cover the difference.

Therefore, storage levels are important, but we must also consider how consumption and ongoing gas supply might look, as a limited margin for error means hiccups in either could have drastic effect. To simulate what could happen, we model changes in gas storage levels through Equation (1) using national level gas production, consumption and import statistics (Figure 1). With a reasonable fit, we can attempt to make some assertions and stress test individual components. Principally, Germany has to contend with the possibility of extra cold weather which could drive up consumption, and lower than normal net gas imports if dwindling Russian supplies cannot be replaced.

(1) ∆Storage = Domestic Production + Net Imports – Consumption

Source: Record, Eurostat, Statistisches Bundesamt, Gas Infrastructure Europe.

First let’s establish a baseline. If consumption and supply are in line with historical norms from here, Germany looks likely to meet its 1st October target of 85%, and should reach its 1st November target of 95%, with gas stored topping out in October as seasonal consumption starts to pick up. Thereafter, gas levels would bottom out at safe levels. However, if the winter turns out to be particularly cold, we estimate that consumption could jump by up to an extra 40 TWh, which is around 20% of current storage. In normal circumstances this could be met through additional imports, however that might not be possible this year. With no adjustment to source additional gas or substitute energy mix, gas levels would reach uncomfortable levels but with shortages avoided due to Germany’s anticipated bumper storage levels (topping out around 35 TWh higher than normal). We estimate that around 5% demand rationing would bring gas levels back to the baseline

Source: Record, Eurostat, Statistisches Bundesamt, Gas Infrastructure Europe, Germany’s National Meteorological Service. Consumption and net imports modelled on median over past five years with cold weather shock consumption modelled using minimum monthly temperatures across the German states and 25th percentile temperatures in the winter months.

But what of constrained supply from Russia over the winter? It is no secret that pipeline flows from Russia are a trickle of pre-invasion levels. For example, the key Nord Stream 1 pipeline running under the Baltic Sea currently operates at 20% capacity. Following disruptions from planned maintenance in July, further maintenance is expected for a few days at the end of August, reviving concerns that flows may stop altogether. Despite these disruptions, Germany over the summer has filled gas levels at a faster rate than in prior years. The consumption and import breakdowns for July and August are not yet available, though this has likely been achieved by some initial rationing and increased supply from energy partners including Norway, Belgium and the Netherlands.

If Germany has been able to replace lost supply you may be wondering what all the fuss is about. The problem lies in the nontrivial flows from Russia that could be yet be targeted; it is worth remembering that as Russia’s energy-related budget revenues rise, only around 20% is from natural gas (in 2021), making it cheap leverage. Focusing on what remains of Nord Stream 1 supply as well as the Sudzha and Sokhranivka pipelines crossing Ukraine, we estimate that Russia could halt up to an additional 10-15 TWh per month. If we subtract that from normal seasonal variations (i.e. making the potentially pessimistic assumption that Germany’s imports return to normal levels), gas reservoirs could run very low in the new year, particularly if there is very cold weather (Figure 3).

The German government is not without ideas and is seeking to mitigate the impact through a mixture of supply and demand measures. On the supply side, the main effort is fast-tracking four new floating storage and regasification units to import liquefied natural gas (LNG), with one expected to be operational by the year end. Assuming successful procurement from world markets (e.g. the US, and potential deals with Qatar and Canada) it is thought that this could add up to 10 TWh supply per month from the new year. In addition, to prevent exacerbating shortages, the country’s grid operator is assessing whether three remaining nuclear plants can remain switched on beyond planned closure in December – but this is only to prevent the situation from worsening.

Source: Record, Eurostat, Statistisches Bundesamt, Gas Infrastructure Europe, Germany’s National Meteorological Service. Consumption and net imports modelled on median over past five years with cold weather shock consumption modelled using minimum monthly temperatures across the German states and 25th percentile temperatures in the winter months.

It’s certainly a start but if our stylised scenarios bear any resemblance to reality and Russia did decide to cut remaining gas supplies, there may not be enough gas to see Germany through the winter. Therefore, the EU’s agreement to cut demand by 15% seems sensible if only as an incredibly economically expensive insurance strategy against Russian cuts, but appears necessary in view of the additional risk of cold weather. We can hope for Europe that these downside scenarios are overly pessimistic – with so many moving parts we will undoubtedly misestimate some factors and not foresee others, and often these kinds of forecasts can incentivise policy change (e.g. Germany could trade off environmental impact for energy security as per a recent law passed allowing use of oil and coal plants if supply is critical) – but nevertheless our back of the envelope calculations suggest it’s a possibility if not taken seriously.

One can therefore surely understand current market concerns and also why the euro has fallen to parity versus the US dollar. If Germany and Europe did truly face gas shortages, further weakness in the euro could be expected as lower output and higher expected inflation would continue to weigh on the currency via real rates.